Books by Roberta Stoddart

The Storyteller

by Roberta Stoddart

2007

Published by Crapaud Foot, Abigail Hadeed and Roberta Stoddart

Seamless Spaces

by Roberta Stoddart

2000

Published by Crapaud Foot, Abigail Hadeed and Roberta Stoddart

Other Books

A–Z of Caribbean Art

2009

Melanie Archer and Mariel Brown, Editors

Published by Robert & Christopher

Victorian Jamaica

2008

“Introduction” by Wayne Modest and Tim Barringer, Editors

Published by Duke University Press

The Birth of Cool

2016

By Carol Tulloch

Published by Bloomsbury

See Me Here: A Survey of Contemporary Self-Portraits from the Caribbean

2014

Melanie Archer and Mariel Brown, Editors

Published by Robert & Christopher

The Garden Party (celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Bank of Jamaica)

2001

Bank Of Jamaica

Published by Bank of Jamaica

Modern Jamaican Art

1998

David Boxer

Veerle Poupeye

Published by Ian Randle Publishers

Journals

Small Axe 38

2012

‘The Interior Life of Painting: Lebenswelt and Subjectivity in the Work of Roberta Stoddart’ by Gabrielle A. Hezekiah

Published by Duke University Press

Art Nexus No. 32

1999

Publisher and Editor, Celia Sredni de Birbragher

Catalogues

Pressure Kingston Biennial

2022

Published by the National Gallery of Jamaica

“Artist Statement” by Roberta Stoddart and Essay, “Weh Yuh Know ‘bout Presha? On the Popular Aesthetics of Pressure” by Wayne Modest

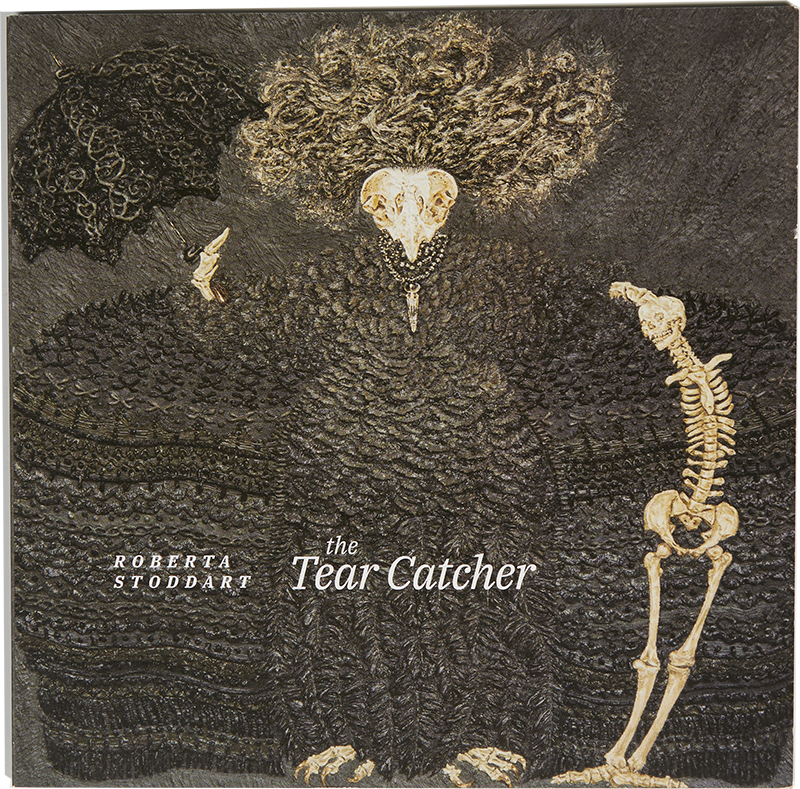

The Tear Catcher

2018

Catalogue of the paintings of Roberta Stoddart from the solo exhibition “The Tear Catcher” at Y Art and Framing Gallery

Published by Crapaud Foot, Abigail Hadeed and Roberta Stoddart

Indigo

2014

Catalogue of the paintings of Roberta Stoddart from the solo exhibition “Indigo” at Y Art and Framing Gallery

Published by Y Art and Framing Gallery, POS, Trinidad

Three Painters

2008

Curated by Susanne Fredricks

Published by 128 Gallerie, Kingston, Jamaica

A Suitable Distance Impressions of Trinidad by Five Artists

2006

Curated by Andy Jacob

Published by Soft Box Studios Limited and Andy Jacob

Politicas de la Diferencia Arte Iberoamericano fin de siglo

2001

Curated by Kevin Power

Published by Generalitat Valenciana

Lips, Sticks and Marks

1998

Published by Annalee Davis for the Lips, Sticks and Marks Collective, c/o The Art Foundry Inc

XXX-eme Festival International de la Peinture

1998

Curated by Marianne De Tolentino

Published by Chateau-Musee Grimaldi, Gagnes-sur-Mer, France

III Bienal de Pintura del Caribe y

Centroamerica

1997

Published by Museo De Arte Moderno, Santo Doming, Dominicana

Writings

-

Dark Exposure: Roberta Stoddart’s The Bertha Room

Isis Semaj-Hall, PhD

May 2023Under the bright sunlight, Jamaica’s mountains are blue, ganja is green, and the waters are aquamarine. Our dawns are pale yellows and soft blues, while our sunsets are a dancing flame of oranges, reds, and purples. In sunny Jamaica, we are taught to never expose our darkness. But Roberta Stoddart, Kingston-born and now a Port of Spain resident, uses her art to confront what was once concealed. Her work encourages viewers to shine light on the hidden uncomfortable truths, as this may be the only way for us to heal.

With a novella that is set in the immediate post-emancipation time of the late 1830s Jamaica as her palette, Stoddart paints the story of Antoinette “Bertha” Cosway, the white-presenting creole protagonist in Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966). Notably, author Rhys (1890-1979) was a white Dominican author who saw herself reflected in Charlotte Brontë’s Caribbean “madwoman in the attic,” a foil of a character in the English classic Jane Eyre (1847). For this reason, Rhys wrote Wide Sargasso Sea, her Jane Eyre prequel, with a sympathetic pen. Like the fictional Antoinette/ Bertha, Rhys understood the double, if not triple rejection of what it felt like to be unwanted by her family and by the black majority in the British colony of her birth, and later also felt unwanted by the English whites when she emigrated to England at the age of sixteen. For Wide Sargasso Sea, Rhys leaned into her own difficult life in order to write empathetically of Antoinette’s.

In an early scene in Wide Sargasso Sea, Antoinette is shown attempting to explain to her soon-to-be husband what it was like growing up in the immediate aftermath of emancipation, a time that left her without any sense of belonging at all. The ex-slaves “hated us” and “[t]hey called us [poor whites] white cockroaches,” she says to the cold Englishman. “One day a little [black] girl followed me singing, ‘Go away white cockroach, go away, go away.’ I walked fast, but she walked faster. ‘White cockroach, go away, go away. Nobody want you. Go away.” This heart-wrenching scene emphasizing her traumatic childhood of color and class ridicule highlights the deep feelings of unbelonging that go on to darken all relationships for Antoinette/ Bertha. For Bertha, having been abandoned by her father, rejected by her mother, despised by her age-mates, and later exploited by her husband, she felt perpetually ostracized and alone.

Wide Sargasso Sea is an important contribution to the study of both Caribbean and English literature because of how the novella humanizes the cruelly depicted “madwoman in the attic” of Brontë’s novel. Similarly, Roberta Stoddart’s The Bertha Room is a new and necessary intervention on Jane Eyre’s darkest character. Stoddart paints Bertha as a sympathetic figure whose development was stunted under patriarchy’s gender rules, and viewers can see this in the infantilized facial qualities of her subjects. Thinking of composition, how and where Stoddart arranges Bertha seems representative of Bertha’s dis/connection to herself and others. And the frigid social environment of colonial Jamaica, is reflected in the cold color schemes and stark unwelcoming backgrounds of the pieces. Stoddart paints scenes that critically imagine the complexity of post-emancipation’s colonial relationships. With Bertha as the recurring subject, Stoddart’s paintings interrogate what happens when people are used, traumatized, discarded, and hidden away like “a memory to be avoided, locked away.”

Standing before the piece titled “Madwoman in the Backroom,” an overt nod to Brontë and Rhys, a viewer is immediately transfixed by the nearly crossed eyes, closed mouth, and open vagina that is Roberta Stoddart’s portrayal of the infamous Bertha character. Stoddart’s Bertha is spread wide and intimately exposed over fifteen square inches of linen. With her dress’s multiple layers gathered in hand, Stoddart’s Bertha squats squarely at the center of a black canvas. Bertha’s sour milk colored face, décolletage, and thighs contrast with the dark color of her skirt, boots, and pubic hair. This “Madwoman’s” sallow skin and pink vulva call our attention, but it is the painting’s blackness that shines brightest. Textured and sculpted by Stoddart’s paintbrush, Bertha’s raven-hued locks reflect what feels like impossible light in this scene of darkest exposure. Standing before the Bertha of “Madwoman in the Backroom,” viewers are forced to reflect. We must reflect upon all the discomfort that we, like Bertha, are conditioned to and supposed to keep hidden under layers of un-confrontable shame, trauma, grief, loss, and guilt.

Rhys’s re-characterized Bertha becomes the vehicle through which Stoddart can investigate the dark space of loneliness and the dark emotional state that surfaces when an identity is broken by colonialism. Laid bare across a total of fourteen distinct paintings, each depicting a sullen-expressioned Bertha in a different anti-tropical setting, Stoddart upends and makes visible the Caribbean’s colonial underside. In this way, The Bertha Room casts a flood of bright moonlight on what was once in the shadows. Stoddart’s work exposes the inky dark of night that we were meant to forget and hide away. These are paintings meant to be seen, displayed, and discussed in the open and in the light. They reveal the hurt that Rhys’s Bertha – and all of us of the Caribbean -- dam behind wide eyes and broken smiles. The Bertha Room pieces reveal the hurt that Brontë’s Rochester – like all exploiters and users of the Caribbean -- tries to conceal behind selfish lies and behind figurative and literal attic doors.

“Everything is too much,” is how Rhys’s Rochester described Jamaica in Wide Sargasso Sea. “Too much blue, too much purple, too much green. The flowers too red.” That kind of rainbow-bright, paradisaic Caribbean colorscape is wholly absent from Stoddart’s portrayal of postcolonial reality and sentimentality. A far cry from the swaying symbols of Caribbean tranquility, in “White Donkey” and “White Cockroaches” the region’s signature palm trees are painted as menacing shadows and as the exposed dry bones of a parasol, respectively. And with titles plucked from the pages of Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, “All of Our Children,” “Back Room Bertha,” “Bertha,” “Doudou Doll,” “Rochester,” “Sand Doll,” “Sleepwalkers,” and “White Cockroach” are painted with skin colored palettes of not-quite-whites and brownish-blacks that seem to whisper with questions about racial purity and race mixing in the Caribbean. While the crimson red intensity of “Immortel” and “Bertha and the Jancro” slip beneath the skin, perhaps colorfully leading us to consider how we, like Bertha and Rochester, play dress-up with our perceived and projected bloodlines.

Roberta Stoddart’s richly complex oil paintings showcased in The Bertha Room, prove that it is dark under the metaphoric flotsam of Wide Sargasso Sea, darker still under the shade of the palm tree’s symbolism, and perhaps darkest of all where racial, familial, patriarchal, and post-colonial trauma festers muted and unseen. No longer can we hide from exposure. The time has come to shine light on the dark secrets of the Caribbean.

___

i. Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. New York: Norton, p 13.

ii. Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. New York: Norton, p 13.

iii. Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. New York: Norton, p 103.

iv. Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. New York: Norton, p 41.

-

Surviving the Dream

My point of Origin is Jamaica. An island of exquisite and improbable beauty, its majestic Blue Mountains, dense dark rainforests, rolling plains and aquamarine seas are unlikely backdrops for its savage past and deep, mysterious secrets. Slavery struck terrible fear into the hearts of both perpetrators and victims alike.

Throughout my childhood and adolescence it was clear that reality was the cornerstone to be avoided at all costs. Investigating nothing, ashamed of everything, we were never to remember. I forgot my Self in the crushing collision of several traumatic histories, in which perpetrators and victims regularly switched roles. Starving for love in a colonial cane field, my sense of belonging grew progressively precarious.

Denying both shadow and light, I stifled my separation and suffering. I was dealt ‘a deep amnesiac blow’1. Desperation was mine. Deep inside I felt like Charlotte Bronte’s ‘Bertha’2, Jean Rhys’ ‘White Cockroach’3, Michelle Cliff’s ‘Madwoman In The Back Room’4.

Emotional drunks fight fear with ethanol and fire. My blood comes to the boil, a red hurricane raging and roaring along the gullies to the sea. Wounded birds are restless and fearful creatures, trembling in idolatry and envy before the status symbols of their culture.

Embracing my spiritual identity, mine is the lifelong process of reclaiming and accepting all of who “I Am”. Seeking to make sense of Caribbean pathologies, I strive to create work as a whole person. What becomes urgent is the process of authentically mapping my original and unique journey of healing and awakening. By doing so I hope to stimulate conversations around what is universal. My work, therefore, is the fire through which I journey to connect to reality and to love. Ultimately, God may be what “I Do”, as well as what “I believe”5.

Copyright Roberta Stoddart 2006/2022

1. Michelle Cliff, Abeng, 1984

2. Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre, 1847

3. Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966

4. Michelle Cliff, The Store Of A Million Items, 1998

5. Roberta Stoddart, The Storyteller, 2007 -

Trauma. Fear. Shame. Loss. Grief. These monumental forces have formed the unrelenting pressures of my lived reality in Jamaica since birth. I consider many questions in my work, in my endeavor to understand and survive deeply felt historical wounds and everyday tensions. In Jamaica there are intense pressures around Race. Class. Gender. Sexuality. Financial and Social Inequity. Cruelty. Brutality. Belonging. When confronted with such sustained pressure, how do we discover our true identities? When we are overwhelmed, how do our feelings and wounded selves manifest? Is this madness a sane response to an insane world? What are the forces that apply this pressure, and how can the human spirit survive it? How can one live an authentic spiritual life without sleeping or dying in the midst of often crushing Pain?

Embracing my spiritual identity, mine is the lifelong process of reclaiming and accepting all of who “I Am”. Seeking to make sense of Caribbean pathologies, I strive to create work as a whole person. What becomes urgent is the process of authentically mapping my original and unique journey of healing and awakening. By doing so I hope to stimulate conversations around what is universal. My work, therefore, is the fire through which I journey to connect to reality and to love. Ultimately, God may be what “I Do”, as well as what “I believe”.

An outline of my three artworks in Pressure:

It must be a Duppy or a Gunman (1998), titled with a borrowed, well known lyric, was motivated by a visit to my Black great-grandmother’s grave in a dilapidated graveyard, and by a dead gunman I envisaged after hearing the spray of bullets on that same day. Thinking about the lack of Love in memoriam, the quickness with which Death can come and its inevitability, I decided to marry the two themes. Duppy is also my first known painting to utilize the color “black” mixed from a variety of blue, red, and yellow paints.

Madwoman in the Back Room (2008) is a portrayal of Jane Bronte’s Bertha from my 2008 series Full Moon Madness. In 1834 Antoinette Cosway, or Bertha, was a White creole outcast incapable of belonging to the Europe of her ancestors or to Jamaica, her birthplace. She is a “white cockroach” to the Blacks who hate her. Englishman Edward Rochester weds Bertha and refashions her into a raving madwoman on their honeymoon. Back in England, Rochester locks her away in his attic. Full of terror, rage and anguish, Bertha sets fire to her husband’s estate, killing herself and maiming him. In this work, Bertha has become completely unhinged, exposing herself as a deranged exile who has lost touch with her authentic self. Shame. Guilt. Rage. Grief. Loss. Suffering. On the surface, Bertha can fit neatly into a confluence of themes that form the bedrock of Caribbean social, political and cultural society and institutions. But Bertha cannot be simply reduced to a perpetrator of atrocities against the enslaved, as solely a woman of privilege, or to predictable feminine stereotypes. Bertha is also a victim of an oppressive patriarchal society.

Sleepwalkers (2009-2017), a large narrative, spanned a period of 8 years in the making. It further explores the concept of Full Moon Madness — that our limited conditioning puts us to sleep, and we long to awaken to our authentic selves and fulfill our potential. In Sleepwalkers, moonlight illuminates the honeymoon party and the dark, eerie landscape. The characters are ever‑fearful of zombification and the loss of their deluded selves. They are conditioned to survive. Literary inspirations for Sleepwalkers are Charlotte Brontё’s bleak Gothic novel Jane Eyre, Jean Rhys’s haunting supernatural prequel Wide Sargasso Sea, and the Jamaican writer Michelle Cliff. My use of paint itself is sculptural in quality and symbolizes the unrelenting build-up of the psychological and emotional weight of the past and its burdened descendants. Moonlight only fleetingly illuminates the darkness of this permanent night.

-

The Sonic Life of Pressure

Excerpt:

Artist Roberta Stoddart has also long been engaged with similar themes. In her work, the question of pressure involves, among other things, the complexly entangled ways that colonialism continues to haunt the material lives of many Jamaicans—indeed, continues to haunt us all today. Negotiations of racialised, gendered, and classed belonging are recurring themes in her work, vividly linking past and present. These are not new themes. In works such as I Am (1999) and The Odd Couple (1999–2000), made more than twenty years ago, Stoddart explores questions of homelessness, vagrancy, and the vulnerability of people whose lives are treated as disposable. This disposability of life has a long history in Jamaica, and the Caribbean, where colonialised lives, dehumanised, were regarded as being of less value, replaceable.

Her exploration of vagrancy is not limited to the body. For example, in her large-scale “history painting,” Sleepwalkers (2009–2017), included in this exhibition, Stoddart draws inspiration from writers Charlotte Brontë, Jean Rhys, and Michelle Cliff, to offer a vantage point from which to explore how the past lives on in the present: as a burden, as pressure on both the individual and society more broadly. This forms part of an ongoing exploration of a kind of spiritual vagrancy, especially of the contemporary “creole” white subject positioned within the afterlives of colonialism. This painting possesses a dreamlike quality, alluding to the hallucinatory landscapes of the European surrealists but in a distinctively Caribbean setting, with Spanish moss in the moonlit trees. The ghostly human figures and disquieting animals confront us with their enigmatic gazes, reminding us of the psychological dimension that is always a part of her work. The dreamworld that we enter invites us to consider the complex interiority of her subjects, black, brown, and white, positioned before us as in a nineteenth-century conversation piece. Yet this interiority is not simply about individual characters. Here Stoddart brings past and present together, revealing history’s defining role in the present. This work, like her corpus more broadly, connects the individual to larger structures of social relations impacted by the colonial past, by slavery and the world it created: individual to family, family to society, all implicated within this history. As with Stoddart’s allusions in Madwoman in the Back Room (2008) to Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre and to Jean Rhys’s expansion of that narrative in Wide Sargasso Sea, Sleepwalkers attunes us to how pressure works on our mental health, to the working of misogyny and patriarchal power that creates spiritual vagrants, especially of women. In the struggle against such pressure, we fight against the long, protracted, zombified sleep that always looms over us.

It is in her work It Must Be a Duppy or a Gunman, however, that Stoddart combines questions of the sonic with those of the visual, attuning us to the sonic life of pressure. She recalls that this work was motivated by visiting the graveside of her black great-grandmother and, on the same day, hearing the sound of gunshots, the sound of spraying bullets. While the duppy, the (haunting) spirit in the work’s title, recalls death and mourning, but also pasts and the wandering of past spirits in the present, the gunshots bring us squarely into the present: shata-tat-tat is the soundscape for many urban poor in Jamaica. It Must Be a Duppy or a Gunman borrows its title from that of a 1970s popular Jamaican song that humorously recalls the response to encountering ghosts.

Pressure, in Stoddart’s works, then, becomes capacious in its quality and impact, affecting us all, even if as differently constituted subjects. She reminds us that in our postcolonial present, which some scholars have described as a moment of post-memory, the long, drawn-out afterlives of the colonial past affect us all. In encountering her work, we are invited to reconsider whether limited notions of perpetrators or victims, of white or black, can fully comprehend the complexity of worlds that colonialism made. We are all implicated subjects under pressure.

-

Roberta Stoddart proposes a similar excavation of the colonial past in the present, even while she, too, explores her personal history of family, ancestry, sexuality, and country. Her work pushes beyond histories or national narratives that seek to exclude some people based on racial or sexual subjectivities. Much of Stoddart’s work is animated by a recurring concern for questions of mental illness, shame, addiction, and codependency, experiences that, for Stoddart, are “all symptoms and outcomes of patriarchal histories and values.” 77 Personal exploration is abstracted to a more universal story, interrogating our common condition of living with the disturbing past. In this way, Stoddart’s art proffers an urgently political stance for the present. Issues surrounding racial and political subjectivities intertwine as she questions the politics of belonging in contemporary Jamaica. In Privy to the Adventures of Nation Building (fig. I.23), created shortly after Stoddart returned to Jamaica in 1991 after a long period abroad, Queen Victoria and Jamaica’s then governor-general, Sir Howard Cooke, the official representative of the Queen (Elizabeth II is Jamaica’s head of state under the Commonwealth system), are seated adjacent to each other within a corked bottle. Both are regally dressed. A ship is also inside the bottle, in the background and seemingly moored on the sand. Stoddart recalls the tradition of sailors placing messages in a bottle, transmitting a communication from the past to the present. The mysterious coral setting perhaps locates the image in the tropics, in Jamaica. The sepia hue gives the figures color; however, this coloring also renders the image eerie, even ghostly. Queen Victoria fixes Cooke with a watchful and serious gaze, while Cooke stares out of the image at the viewers with the authoritative air of someone carrying out his duty. As a black Jamaican dressed in ceremonial regalia associated with the British Empire, Cooke takes on the character of what Homi Bhabha has called a “mimic man.” 78 His left hand holds what seems to be a canoe — a small, powerless boat in comparison to the large ship in the background exemplifying Britain’s naval power — while the length of cord from a noose lying in a bundle on the right passes over his right hand, in which he holds a scrolled piece of paper. He is both authoritative and absurd, a figure of menace and melancholy. A statement about the vestige of colonial rule that retains the British monarch as Jamaica’s head of state, still watching over the Jamaican people, the work also comments on capital punishment and the role of the Privy Council — a group of advisers to the British monarch that dates to Tudor times — as Jamaica’s highest court. Stoddart’s work finds pathos in the condition of a country trapped in a struggle to come to grips with the past in the present.

In Queen Victoria’s Veil (1995), Stoddart engages with Victorian values, especially those regarding lesbian identity. A miniature image of Stoddart herself in the crook of Victoria’s elbow, covered only by the Queen’s transparent veil. Both Stoddart and Victoria appear to be under the sea: a stream of bubbles moves upward from Victoria’s mouth and from Stoddart’s hair, which moves freely in water. Shells decorate both women’s hair. With her left hand, Stoddart holds a pendant at Victoria’s neck. Ornamented with what seems to be a vulva, the pendant is again veiled by the translucent fan Victoria holds. Here Stoddart draws attention to the veiled presence of Victorian prudery in contemporary Jamaica that seeks to govern, and even proscribe, lesbian identity, in much the same way that Victorian Britain applied repressive and often hypocritical restrictions on sexuality and sexual behavior.79 Mapping onto a Jamaican present that is rife with intolerance for homosexuality and at the same time tries to define the nation as black to the exclusion of other racial identities, Stoddart again draws attention to how exclusionary politics, whether through Victorian prudery or contemporary racialization, continue to do violence to some subjects within Jamaican society.

-

Over the past few years, I’ve done a number of studio visits with painter Roberta Stoddart. On one of these visits, in 2012, she shared with me, as she often does, a few of the things that she had been reading – bits of text to which she turns as guidelines to her daily living; thoughts that can sometimes affect her painting. One of those things has stayed with me for some time now: Spirituality enters through shadow. Although a fairly simple concept to grasp, in spite of its somewhat abstract nature, an unpacking of this thought can help in understanding Stoddart’s “Behind the Bridge” (2012–2013) series of paintings.

For the past two decades, Stoddart has created various series of work in which there is encompassing darkness. In certain instances this darkness is literal, as is the case with her "Full Moon Madness" (2008) series, in which the artist mined her complicated history to address – forthrightly, uncomfortably, beautifully – difficult issues like addiction, mental illness, neglect and sexism. The darkness in this work manifests not only in backgrounds and garments but, more profoundly, in a figurative or psychological sense, with an ever-present suggestion of things hidden or threatening. Most recently, Stoddart painted the "Indigo" (2013–2014) series, which, she notes, came out of hurt and grief and an eventual “acceptance of many losses” in her life. Also characterised by dark colours – the deepest, almost-black blues in backgrounds and skies – the paintings in this series often contain tiny points of light that hint not only at hope, but also at our connection into a system that is so much larger than ourselves.

On the other hand, taken on the surface, Stoddart’s Behind the Bridge series is, comparatively, full of light. First looks at this series could lead to the interpretation that the artist has turned away from a more complicated examination of self to focus instead on the simple, everyday lives of people who live in a particular area of East Port of Spain known as “behind the bridge”. When Stoddart had just embarked on painting this series she noted: “In paintings to follow, I will endeavor to create works which will in some way, I hope, reflect aspects of the lives of people who live on the fringes and margins of Port of Spain society.”

Behind the Bridge would have taken Stoddart, literally, to an area of the city into which most people would not willingly venture – and into the lives of those in the shadow. Her very act of going there to observe and document the lives of people considered to be on the fringes and outskirts of society – people linked in the public consciousness to violence, gangs and disenfranchised living – shows the artist’s bravery in exploring. This geographical exploration is symbolic of another type of exploration – of Stoddart’s ability to face fears and to step outside of her comfort zone in order to make connections with strangers as she questions the ways in which we treat others, but also how we treat ourselves. “I kind of like [this series] more for the Trinidadian feel of it; on the surface, it is very everyday,” she has noted. “My pull has always been how we could make things better collectively. A good place to start would just be to continue on this journey of trying to free myself from some of my own narrow, limiting ideas of what’s important in my own life.”

The Behind the Bridge series consists of 10 paintings, all of which freeze people, buildings and scenes in motion during daytime activities. Stoddart has said of one work in the series, Lucky Jordan: “This painting gives us a certain view of the environment surrounding the infamous landmark ‘Lucky Jordan Recreation Club’. This drinking parlour is situated upstairs at the corner of Prince and George Streets, deep in Port of Spain. Inside, the walls are painted every color imaginable, which ostensibly, should not go together. And yet, the atmosphere feels harmonious and completely original. In one room both men and women gamble wappie. Throughout the rest of the rooms, patrons consume large quantities of rum and other liquor at all hours of the day and night.”

In each of the paintings in Behind the Bridge we can feel Stoddart’s care and wonder. In each work a marked mastery of paint is evident – in her dramatic skies and her ability to render metal work, wrinkles, muscles, hair and the like with precision and skill. What is also here, and perhaps more difficult to feel and understand, is an indication of spirituality entering through shadow – a reconsidered and optimistic view of a place considered bleak and hopeless. Here is Stoddart’s transcendental way of looking at darker material in a manner that is deliberately, consistently without judgment or pretense but infused instead with beauty and an appreciation of the everyday. And, of course, light – after all, there cannot be shadow without it.

-

my journey towards self-acceptance determines my allegories. in painting the world around me, i search for an independent figurative vision of what is inwardly known at the crossroads of the singular and the connected.

—Roberta Stoddart, artist statement, Seamless SpacesJamaican painter Roberta Stoddart has created a body of work in which personal and social histories intertwine to produce a contemplative response to what might be described as notions of enduring catastrophe. Stoddart seeks to recognize a horizon of collective experience and shared subjectivity mediated through historical specificity and grounded in consciousness and the transcendent. Her work acknowledges the complex and interconnected character of lives in the traumatic aftermath—and continuance—of history. Yet it does not seek to come to terms with that history by externalizing its causes and effects. Rather, the work addresses the psychic legacy of slavery and involves a process of deep questioning. Stoddart delves into psychological spaces. She recognizes the damage engendered by relations of slavery, and her questioning poses a challenge to neat categorizations of self and other. There are paintings in Stoddart’s portfolio that tackle the question of slavery frontally—Black Pearls (1998) and Tools of the Trade (1996), which utilize the symbol of the slave ship—but it is in the paintings that resist the contemporary iconography of slavery that Stoddart’s work is perhaps at its best.1

Stoddart’s work is deeply personal and charts a journey of transformation and consciousness. This consciousness is at first unique and individual—not collective—and is accessed through a patient process of internal work and reflection. In her writing, Stoddart has referred to her family history and the supports and silences that shaped her development. Understanding her experiences as a white creole woman in the Jamaican and wider Caribbean context is one part of this journey. Stoddart reveals that her visual narratives of white creole Jamaica are an attempt to establish connections between various aspects of herself, Jamaican culture and history, and the essential identity (self) that we all possess.2 This is particularly evident in work produced in 1999 and 2006–7. Stoddart’s series on homeless people in Port of Spain in 1999 and the later series In the Flesh on albino people in Trinidad both display a need to connect with the discarded aspects of ourselves—to recognize ourselves in the other and the other in ourselves. Her work aims to recognize wholeness—to recognize and restore. In dialogue with Cathal Healy-Singh, the discussion focuses on the spiritual as Healy-Singh draws parallels between Stoddart’s work and the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta. One has the sense that Stoddart is attempting to transcend imposed boundaries and through this to access what Healy-Singh refers to as the Real. Stoddart writes, “value comes from the reservoir of consciousness. . . . when this truth punctures the membrane that appears to separate the physical world from the world of consciousness then all is one and there is no longer separation.”3 Stoddart does not claim to equate the truncation of the spirit with the material experience of homelessness.4 But her concern with acceptance, healing, and belonging creates conditions under which the terms of each of those experiences might be recognized. Stoddart’s work is concerned with contemporary manifestations of historical questions and experiences, with questions of apperception rather than mere perception. Stoddart’s eye brings to the viewer an internal question rather than a portrayal, concept, or idea. By this I do not mean that Stoddart has gained access to the other’s soul, but I do mean to suggest that she has tapped into a certain experience that is presented to the viewer as both typical and singular. The world that Stoddart perceives is of course relayed to the viewer after layers of translation, but I would suggest that in her attempt to reveal the essence of each character and to reveal the essence of “that which we all are,” she accesses a condition that we might properly characterize as human and damaged, transcendent, and whole.5Stoddart seeks first an understanding of her own vantage point—an understanding of how the world has come to exist for her—and how her experience of the world is constitutive both of her own subjectivity and of the system of relations that structure the possibilities for the condition of being human in this Caribbean space. Stoddart’s work reveals a Lebenswelt, or lifeworld, as we might think of it in the Husserlian sense—an “intuitive surrounding world of life, pregiven as existing for all in common”—that underlies all our assumptions but that remains largely unthematized.6 Stoddart questions the assumptions that underlie our interpretation and experience of the everyday. She challenges the silence and the taken-for-granted in our understanding of the effects of catastrophic history. She investigates the consciousness that produces our world and in so doing thematizes the Lebenswelt. Stoddart begins with the self as a personally held experience and moves outward toward the experience of subjectivity held by the other. Memory, innocence, shame, and loss are all a part of this process. Stoddart’s work—in particular, the paintings in her most recent series Full Moon Madness—displays parallels to the notions of transcendental ego and transcendental subjectivity in Husserl’s phenomenology. In this essay I would like first to point to several paintings indicative of Stoddart’s journey, and then to elements of the movement toward intersubjectivity and the ways in which Husserl’s lifeworld might add insight to our interpretation of Stoddart’s process.