The Bertha Room (1996–2023)

Artist’s Statement

Roberta Stoddart, 2018–2023

Developed over nearly three decades, these paintings feature my ongoing interest in the character Bertha. Literary inspirations for Bertha are Charlotte Brontё’s bleak Gothic novel Jane Eyre, Jean Rhys’s haunting supernatural prequel Wide Sargasso Sea, and the Jamaican writer Michelle Cliff.

-

In 1834 Antoinette Cosway, or Bertha, was a white creole outcast incapable of belonging to the Europe of her ancestors or to Jamaica, her birthplace. She is a White Cockroach (2006) to the Blacks who hate her. Englishman Edward Rochester weds Bertha and reshapes her into a raving madwoman on their honeymoon. Back in England, Rochester locks her away in his attic. Full of terror, rage and anguish, Bertha sets fire to her husband’s estate, killing herself and maiming him. In Madwoman In The Back Room (2008), Bertha has become completely unhinged, exposing herself as a deranged exile who has lost touch with her authentic self. Shame. Guilt. Rage. Grief. Loss. Suffering. On the surface, Bertha can fit neatly into a confluence of themes that form the bedrock of Caribbean social, political and cultural society and institutions. But Bertha cannot be simply reduced to a perpetrator of atrocities against the enslaved, as solely a woman of privilege, or to predictable feminine stereotypes. Bertha is also a victim of an oppressive patriarchal society, and of a society constructed on rigid class and race hierarchies.

Bertha And The Jancro (2023), depicts Rochester’s wedding to Bertha. Rochester is the Jancro (John Crow), the derogatory term given to British colonisers by the enslaved in Jamaica. The Jancro, with his vulture skull and in his red military outfit, is seen as both a scavenger and a portender of death. Bertha’s red dress, mirroring the red in Rochester’s attire, has multiple meanings: red for the early bloom of romance during their courtship; for when she was dressed in red by relatives who never allowed her out for more than minutes at a time at twilight so that any hints of her madness and her mixed racial background could pass unnoticed; red for the many fires she set ablaze in Rochester’s mansion; red for the blood spilled by her suicide jumping to her death from the roof; and red as symbolic of her mental anguish, her suffering, her rage. Behind the couple is a local Guango tree burdened with “Spanish Moss”, a wild Bromeliad, haunting the setting. Rochester/ Jancro’s walking stick crosses diagonally in front of Bertha as if to keep any sudden movements of hers in check – a sign of more patriarchal control to follow.

Sleepwalkers (2009-2017), a large narrative, spanned a period of 8 years in the making. It further explores the concept of Full Moon Madness — that our limited conditioning puts us to sleep, and we long to awaken to our authentic selves and fulfill our potential. In Sleepwalkers, moonlight illuminates the honeymoon party and the dark, eerie landscape. The characters are ever‑fearful of zombification and the loss of their deluded selves. They are conditioned to survive. My use of paint itself is sculptural in quality and symbolizes the unrelenting build-up of the psychological and emotional weight of the past and its burdened descendants. Moonlight only fleetingly illuminates the darkness of this permanent night.

Dark Exposure: Roberta Stoddart’s The Bertha Room

Isis Semaj-Hall, PhD, May 2023

“Rhys’s re-characterized Bertha becomes the vehicle through which Stoddart can investigate the dark space of loneliness and the dark emotional state that surfaces when an identity is broken by colonialism.”

-

Under the bright sunlight, Jamaica’s mountains are blue, ganja is green, and the waters are aquamarine. Our dawns are pale yellows and soft blues, while our sunsets are a dancing flame of oranges, reds, and purples. In sunny Jamaica, we are taught to never expose our darkness. But Roberta Stoddart, Kingston-born and now a Port of Spain resident, uses her art to confront what was once concealed. Her work encourages viewers to shine light on the hidden uncomfortable truths, as this may be the only way for us to heal.

With a novella that is set in the immediate post-emancipation time of the late 1830s Jamaica as her palette, Stoddart paints the story of Antoinette “Bertha” Cosway, the white-presenting creole protagonist in Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966). Notably, author Rhys (1890-1979) was a white Dominican author who saw herself reflected in Charlotte Brontë’s Caribbean “madwoman in the attic,” a foil of a character in the English classic Jane Eyre (1847). For this reason, Rhys wrote Wide Sargasso Sea, her Jane Eyre prequel, with a sympathetic pen. Like the fictional Antoinette/ Bertha, Rhys understood the double, if not triple rejection of what it felt like to be unwanted by her family and by the black majority in the British colony of her birth, and later also felt unwanted by the English whites when she emigrated to England at the age of sixteen. For Wide Sargasso Sea, Rhys leaned into her own difficult life in order to write empathetically of Antoinette’s.

In an early scene in Wide Sargasso Sea, Antoinette is shown attempting to explain to her soon-to-be husband what it was like growing up in the immediate aftermath of emancipation, a time that left her without any sense of belonging at all. The ex-slaves “hated us” and “[t]hey called us [poor whites] white cockroaches,” she says to the cold Englishman. “One day a little [black] girl followed me singing, ‘Go away white cockroach, go away, go away.’ I walked fast, but she walked faster. ‘White cockroach, go away, go away. Nobody want you. Go away.” This heart-wrenching scene emphasizing her traumatic childhood of color and class ridicule highlights the deep feelings of unbelonging that go on to darken all relationships for Antoinette/ Bertha. For Bertha, having been abandoned by her father, rejected by her mother, despised by her age-mates, and later exploited by her husband, she felt perpetually ostracized and alone.

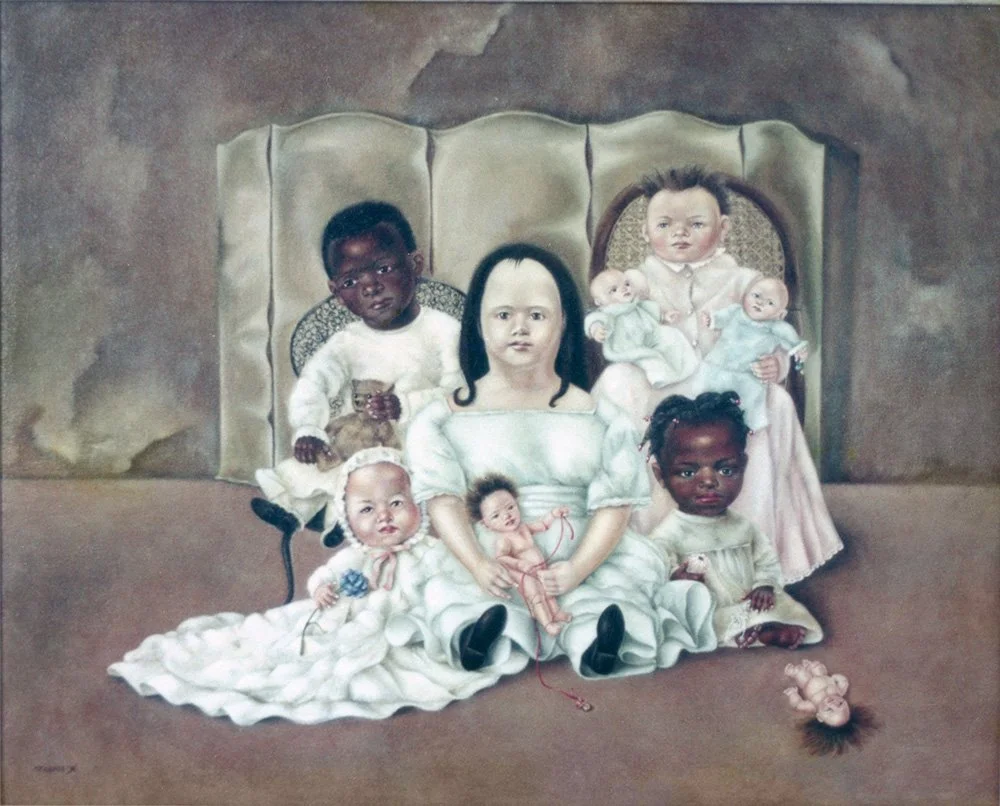

Wide Sargasso Sea is an important contribution to the study of both Caribbean and English literature because of how the novella humanizes the cruelly depicted “madwoman in the attic” of Brontë’s novel. Similarly, Roberta Stoddart’s The Bertha Room is a new and necessary intervention on Jane Eyre’s darkest character. Stoddart paints Bertha as a sympathetic figure whose development was stunted under patriarchy’s gender rules, and viewers can see this in the infantilized facial qualities of her subjects. Thinking of composition, how and where Stoddart arranges Bertha seems representative of Bertha’s dis/connection to herself and others. And the frigid social environment of colonial Jamaica, is reflected in the cold color schemes and stark unwelcoming backgrounds of the pieces. Stoddart paints scenes that critically imagine the complexity of post-emancipation’s colonial relationships. With Bertha as the recurring subject, Stoddart’s paintings interrogate what happens when people are used, traumatized, discarded, and hidden away like “a memory to be avoided, locked away.”

Standing before the piece titled “Madwoman in the Backroom,” an overt nod to Brontë and Rhys, a viewer is immediately transfixed by the nearly crossed eyes, closed mouth, and open vagina that is Roberta Stoddart’s portrayal of the infamous Bertha character. Stoddart’s Bertha is spread wide and intimately exposed over fifteen square inches of linen. With her dress’s multiple layers gathered in hand, Stoddart’s Bertha squats squarely at the center of a black canvas. Bertha’s sour milk colored face, décolletage, and thighs contrast with the dark color of her skirt, boots, and pubic hair. This “Madwoman’s” sallow skin and pink vulva call our attention, but it is the painting’s blackness that shines brightest. Textured and sculpted by Stoddart’s paintbrush, Bertha’s raven-hued locks reflect what feels like impossible light in this scene of darkest exposure. Standing before the Bertha of “Madwoman in the Backroom,” viewers are forced to reflect. We must reflect upon all the discomfort that we, like Bertha, are conditioned to and supposed to keep hidden under layers of un-confrontable shame, trauma, grief, loss, and guilt.

Rhys’s re-characterized Bertha becomes the vehicle through which Stoddart can investigate the dark space of loneliness and the dark emotional state that surfaces when an identity is broken by colonialism. Laid bare across a total of fourteen distinct paintings, each depicting a sullen-expressioned Bertha in a different anti-tropical setting, Stoddart upends and makes visible the Caribbean’s colonial underside. In this way, The Bertha Room casts a flood of bright moonlight on what was once in the shadows. Stoddart’s work exposes the inky dark of night that we were meant to forget and hide away. These are paintings meant to be seen, displayed, and discussed in the open and in the light. They reveal the hurt that Rhys’s Bertha – and all of us of the Caribbean -- dam behind wide eyes and broken smiles. The Bertha Room pieces reveal the hurt that Brontë’s Rochester – like all exploiters and users of the Caribbean -- tries to conceal behind selfish lies and behind figurative and literal attic doors.

“Everything is too much,” is how Rhys’s Rochester described Jamaica in Wide Sargasso Sea. “Too much blue, too much purple, too much green. The flowers too red.” That kind of rainbow-bright, paradisaic Caribbean colorscape is wholly absent from Stoddart’s portrayal of postcolonial reality and sentimentality. A far cry from the swaying symbols of Caribbean tranquility, in “White Donkey” and “White Cockroaches” the region’s signature palm trees are painted as menacing shadows and as the exposed dry bones of a parasol, respectively. And with titles plucked from the pages of Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, “All of Our Children,” “Back Room Bertha,” “Bertha,” “Doudou Doll,” “Rochester,” “Sand Doll,” “Sleepwalkers,” and “White Cockroach” are painted with skin colored palettes of not-quite-whites and brownish-blacks that seem to whisper with questions about racial purity and race mixing in the Caribbean. While the crimson red intensity of “Immortel” and “Bertha and the Jancro” slip beneath the skin, perhaps colorfully leading us to consider how we, like Bertha and Rochester, play dress-up with our perceived and projected bloodlines.

Roberta Stoddart’s richly complex oil paintings showcased in The Bertha Room, prove that it is dark under the metaphoric flotsam of Wide Sargasso Sea, darker still under the shade of the palm tree’s symbolism, and perhaps darkest of all where racial, familial, patriarchal, and post-colonial trauma festers muted and unseen. No longer can we hide from exposure. The time has come to shine light on the dark secrets of the Caribbean.

Bertha and the Jancro (2023), 20 x 20 inches, oil on linen

Immortel (2022), 8 x 5 inches, oil on hardboard

Sleepwalkers (2009–2017), 76 x 55 inches, oil on linen

Bertha and Rochester (2009), two panels each 12 x 6 inches, oil on linen

White Donkey (2022), 10 x 10 inches, oil on hardboard

Doudou Doll (2009), 7 x 7 inches, oil on linen

White Cockroach (2006), 4 x 3 inches, oil on linen on hardboard

White Cockroaches (2008), 10 x 10 inches, oil on linen

Madwoman In The Back Room (2008), 15 x 15 inches, oil on linen

Back Room Bertha (2008), 10 x 10 inches, oil on linen

Soucouyant (2023), 6 x 3 3/8 inches, oil on hardboard

Sand Doll (1996), 10 x 8 inches, oil on linen

All Of Our Children (1996), 20 x 16 inches, oil on canvas